8 min read // Sep '23 - Jul '24 // 11 months // View project source

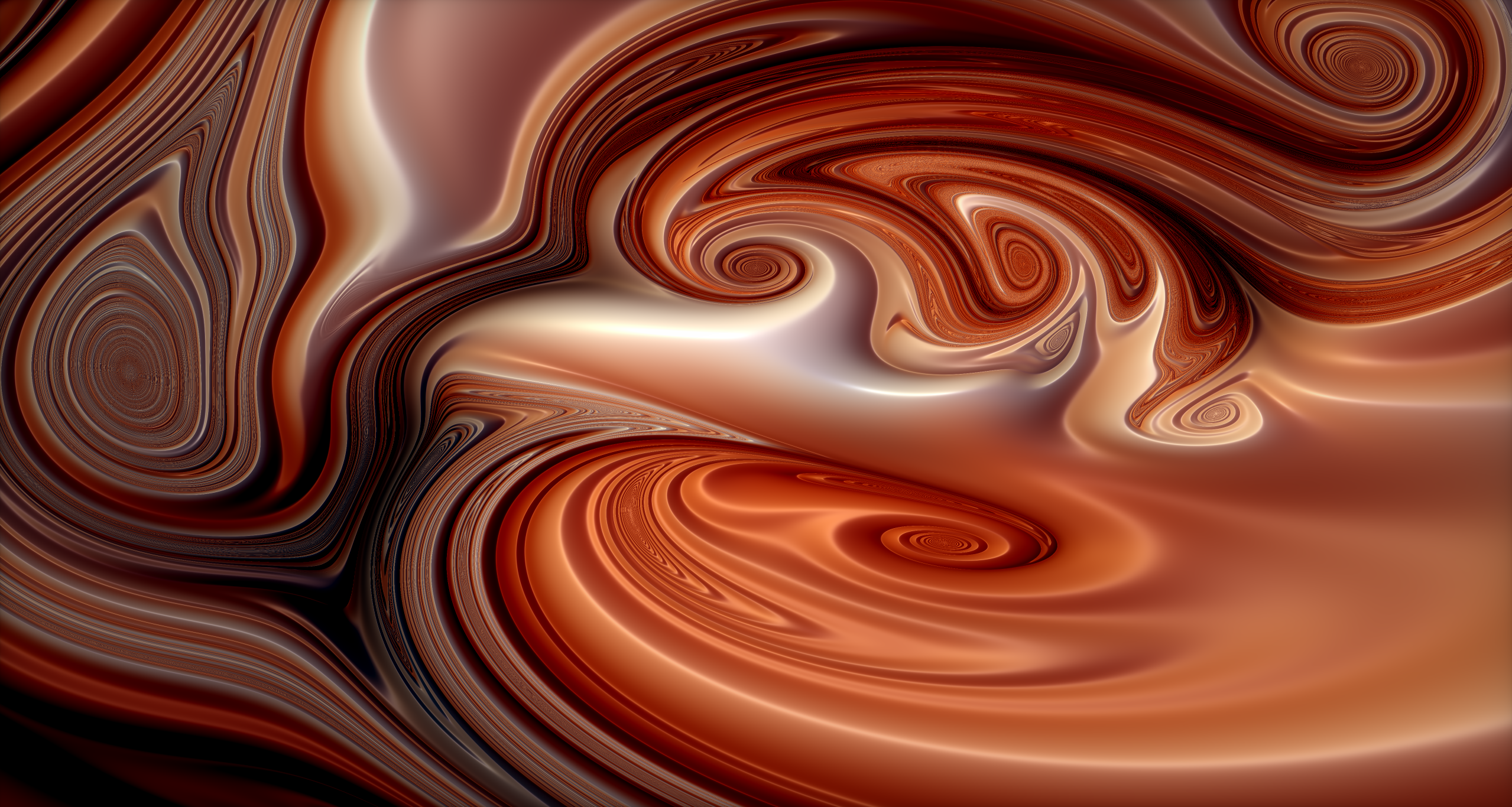

Iterations - inversion 2 ported to C# here

About a year after I started developing SimulationFramework, someone on the discord server suggested adding programmable shaders. I thought this would be a really powerful feature (and it would be very interesting to implement) so I started looking into it. I ended up with a pretty unique and powerful solution, compiling C# to GLSL at runtime.

The Problems with the Usual Suspects

My first thought was to simply allow the user to provide the library some HLSL or GLSL code to run (like p5.js). However, I found this didn't align with SimulationFramework's developer-friction-free design philosophy:

- Requires the user to learn another programming language

- Binding uniforms by name is annoying

- Keeping struct definitions in sync between host and shader code is annoying

- IDE support in shaders is not very good

- Not cross-platform (without bringing in a dependency on a shader cross-compiler)

Enter C#

After evaluating a few options I realized only one language checked every box: C#!

- The user already programming in C#

- It's cross-platform and has great IDE support

- Everything being the same language means that:

- Uniforms can be set directly

- Struct definitions don't need to be duplicated.

Sounds great! Except there are no graphics APIs that accept C# as a shader language. So, like anyone else would in this situation, I wrote my own compiler.

The Plan

The problem was simple: convert C# to GLSL shader code to be run on the GPU. The solution however, was very much not.

First, I had to decide between compile-time and runtime compilation. I found compile-time projects involved a lot of build system or source generator trickery. I didn't want to wrestle with that, and I especially didn't want to force any of that wrestling upon the user.

Also, a lot of its benefits (ie skipping long compile times at app startup) didn't really matter in the context of SimulationFramework, which is meant for building small prototypes quickly. Runtime compilation gives the library full control over the compilation process, allowing me to ensure the user doesn't have to deal with managing separate shader sources or build systems.

Next I had to figure out how to actually retrieve the user's code. I looked into a few solutions, such as System.Linq.Expressions's expression capturing (which only works for lambdas with a single line). I ultimately decided on MethodBody.GetILAsByteArray for a few reasons:

- Simple code from non-user libraries can be included in shaders with little thought

- I avoided needing to parse anything

- I got support for some high level language features (ie switch expressions) for free

The only draw back is now the user code is in CIL (C#'s bytecode language) instead of a syntax tree, this complicates the compiler a lot, but I think for SimulationFramework it's worth it.

The API

I designed the shader API to feel like writing GLSL inside C#.

- All shaders inherit from an abstract base shader class (

CanvasShader) - They override the entry point method (

GetPixelColor(Vector2)). - Uniforms are fields on the class. They're uploaded to the GPU automatically by the library, all the user needs to do is set the field on the shader instance.

- Struct types can be used as long as they're blittable (contain no references). The compiler automatically translates these to GLSL.

- The user can optionally import all shader intrinsics into the global namespace via

using static SimulationFramework.Drawing.Shaders.ShaderIntrinsics;. This way functions likesinandsqrt(and their vector overloads!) are available globally, just like glsl.

Here a simple shader which shades geometry with a solid color:

using SimulationFramework;

using SimulationFramework.Input;

using SimulationFramework.Drawing;

using SimulationFramework.Drawing.Shaders;

class SolidShader : CanvasShader

{

public ColorF colorUniform;

public override ColorF GetPixelColor(Vector2 position)

{

return colorUniform;

}

}Using the shader is as simple as passing an instance of the shader to ICanvas.Fill while rendering:

public override void OnRender(ICanvas canvas)

{

canvas.Clear(Color.Black);

SolidShader shader = new SolidShader();

shader.colorUniform = ColorF.Red;

canvas.Fill(shader);

canvas.DrawRect(0, 0, canvas.Width, canvas.Height);

}The Details: Compiling a Method

The core behavior of the compiler is converting C# methods to shader functions. Starting with the shader entry point, each method's dependencies are added to a queue to be compiled, this way only the entry point and its dependencies get compiled.

The compilation pipeline for a single method consists of a few stages:

- Disassembly

- Control Flow Reconstruction

- Expression Reconstruction

- Post-Processing

- Target Shader Language Emit

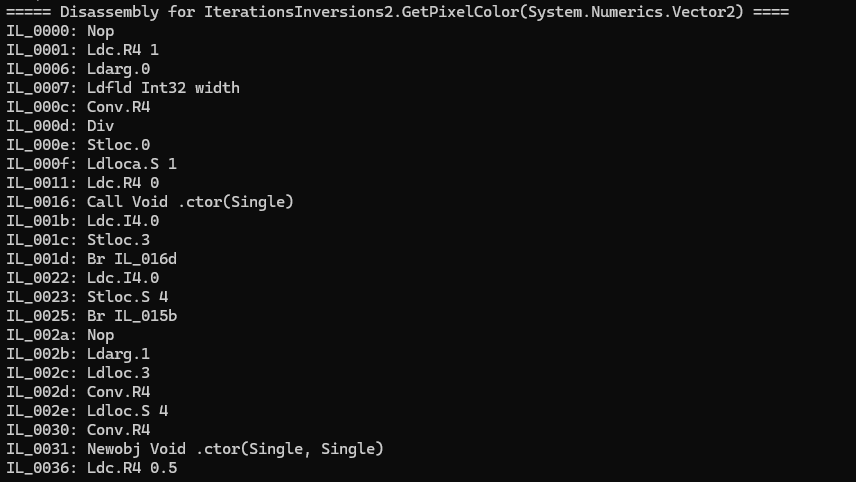

Disassembly

First, the IL from MethodBody.GetILAsByteArray is disassembled into a list of CIL instructions. This was pretty simple to implement since CIL has a relatively simple format and there are a ton of good resources online about it.

CIL for a C# shader disassembled by the compiler

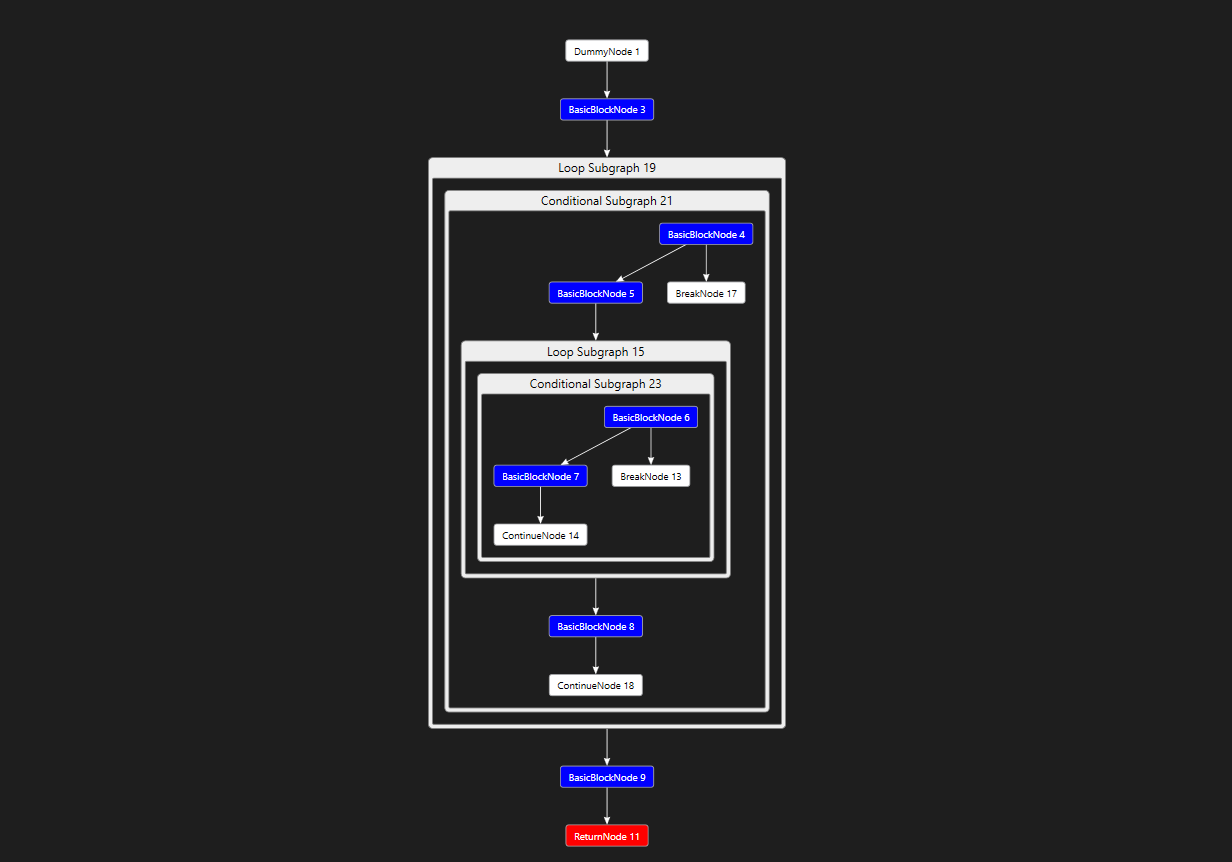

Control Flow Reconstruction

The next step is the most complicated step of the whole process. The problem is that in CIL essentially only has gotos (br and related instructions), while shading languages only have high-level control flow excluding goto statements. My compiler problem had turned into a decompiler problem! I solved this by doing a little control flow recontruction:

- The CIL is broken into basic blocks (sections with linear control flow), creating a control flow graph

- Return blocks (nodes that point to the end of the method) are marked as such

- Loops (any node that dominates its predecessor, meaning execution must flow through the node to reach the predecessor) are replaced with a loop subgraph. Continue and break statements are nodes that point to the head and tail node of the loop, respectively. Then, control flow is recontructed recursively inside the loop (to allow nesting).

- Conditional statements are any node with more than one predecessor. They are replaced with a conditional subgraph, consisting of every node between the original node and point where the program flow reconverges. The same recursive reconstruction applied to loops is then done here.

After a little bit of extra effort required to make everything play nice (look at you break/continue statements), this process finishes with all loops in a standard form and all conditional statements in one of two standard forms (if-style or if-else style).

Debugging Control Flow Graphs

Some of the control flow algorithms came to be pretty complicated and hard to debug. So I wrote a DGML exporter for the shader graphs so they could be opened in visual studio.

A DGML graph from the shader compiler viewed in visual studio

This made debugging issues with the control flow reconstruction about ten times easier. I would have missed a lot of bugs had I not done this. Good debug tools are one of the most underappreciated parts of any project.

Expression Reconstruction

The reconstructed control flow graph along with the basic blocks are then passed the the expression builder. This stage walks the graph, creating a language-agnostic shader syntax tree. It emits control flow as it visits the nodes, then reconstructs full expression from the stack-based IL.

Intrinsics & Intercepts

One problem with users writing shaders in C# is that they will want to use all of their familiar types (ex. MathF). In shader languages, most of the functions here (ie sqrt, sin) are considered intrinsic and provided by the language.

I settled on a compromise: I define a set of intrinsics for shader code, and these intrinsics are decorated with shader intercepts. Shader intercepts tell the compiler to replace calls to the target method with the intrinsic. This way, if the user uses MathF.Sqrt, it simply resolves to ShaderIntrinsics.Sqrt and the shader code emitter can map it to the sqrt glsl intrinsic.

public static class ShaderIntrinsics

{

[ShaderIntrinsic]

[ShaderIntercept(nameof(Sqrt), typeof(MathF))]

public static float Sqrt(float x) => MathF.Sqrt(x);

}This behavior is implemented in the expression builder which resolves methods as soon as call instructions are reached. If the method is the target of an intercept it is replaced with the intercept source method.

Post-Processing

The post processing stage simplifies and optimizes the syntax tree before the emit stage. It does things like remove redundant variables (variables that are set & used once, often output by the C# compiler) and fix ternary expressions which can get incorrectly reconstructed from compiler optimizations.

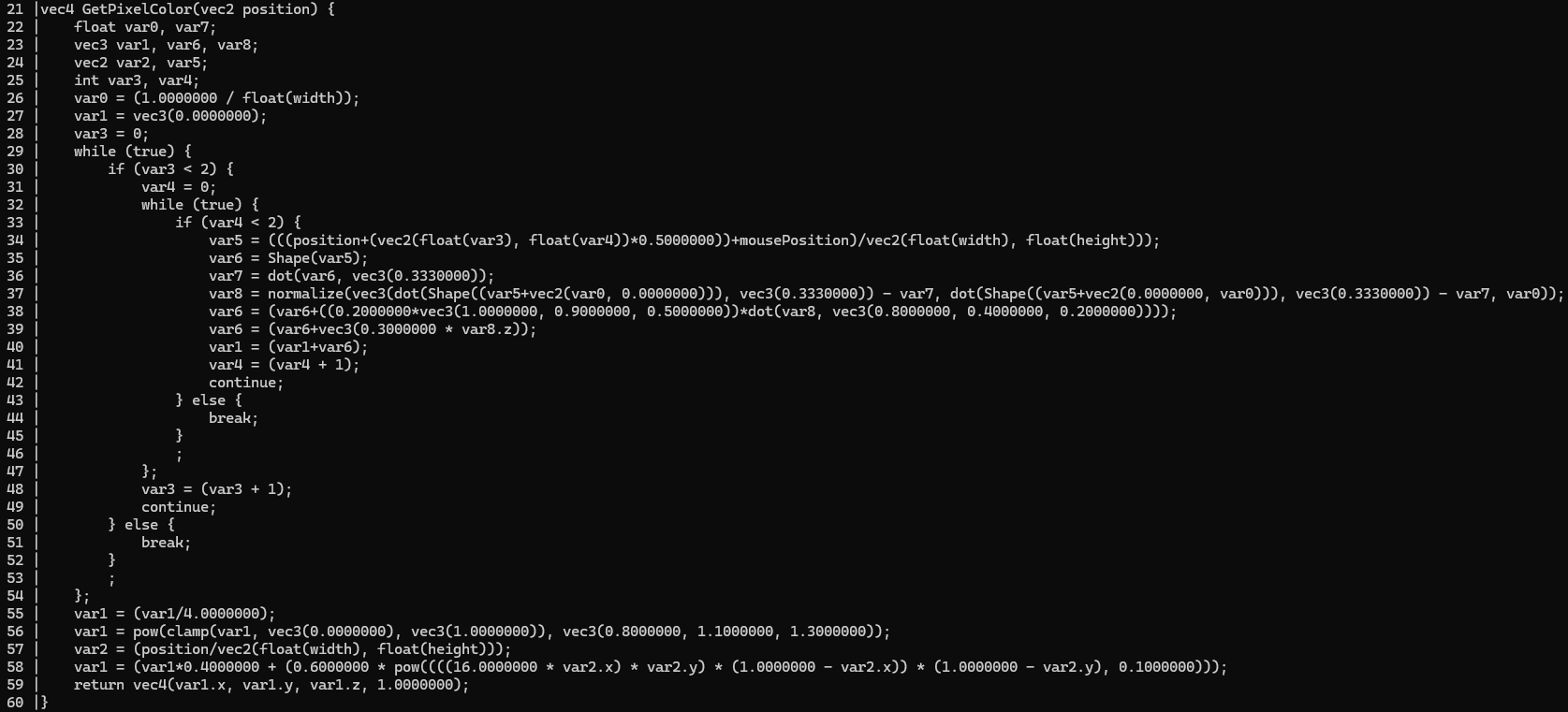

Target Shader Language Emit

The final step of method compilation is to walk the shader tree generated by the expression builder and convert it to shader code for the target platform. This is just a simple graph visitor that writes matching GLSL syntax to a stream as it visits nodes. Some special care was needed to prefix identifiers that conflict with keywords and map intrinsic methods to their language-specific names.,

An example glsl function generated by the compiler. It's not pretty but it's valid GLSL!

The resulting GLSL is really ugly, with a lot of overcomplicated control flow and no local variable names, but it works!

Uniforms and Type Mapping

Whenever the compiler encounters a type it immediately compiles it, mapping it to a ShaderType value. This could mean a few things depending on the type:

- If the type is considered intrinsic (ie

int,Vector2,ITexture) it maps to the corresponding intrinsicShaderTypevalue - If the type is a struct (and not already compiled), the members of that struct are compiled and it is mapped to a

ShaderStructureType - If the type is not blittable (contains references) then an error is thrown since shader languages don't support this

Implementing SimulationFramework.Drawing.Gradient

Once the shader compiler was stable enough, I ported the library's gradient types, LinearGradient and RadialGradient to use shaders. This way, graphics backends would no longer need to provide gradient support.

This led to a problem: gradient types support any number of colors, while shaders only supported uniforms and textures. I needed to access the gradient's array of stops in the shader. The only non-hack solution I could think of here was buffer support.

Shader Arrays

At first, I considered adding an IBuffer type (similar to ITexture). However, I found managing the buffer's lifetime and moving data to/from the buffer were very repetitive tasks that added developer friction. Then it struck me: C# already has a type that looks like a buffer, that every C# developer knows how to use. Arrays!

The idea is: the user accesses the array directly (as a shader uniform) and the library manages the buffers and synchronization. Again minimizing user friction and making iteration time quicker!

The implementation is surpisingly simple! It uses a ConditionalWeakTable to allocate a buffer for every array used in a shader. Whenever an array is bound as a uniform, reads/writes using that array are mapped to buffer load/store intrinsics for the backend to handle. Then, the array's data is copied to the buffer immediately before any draw call is made that uses it. Works like a charm!

SpaceRTS

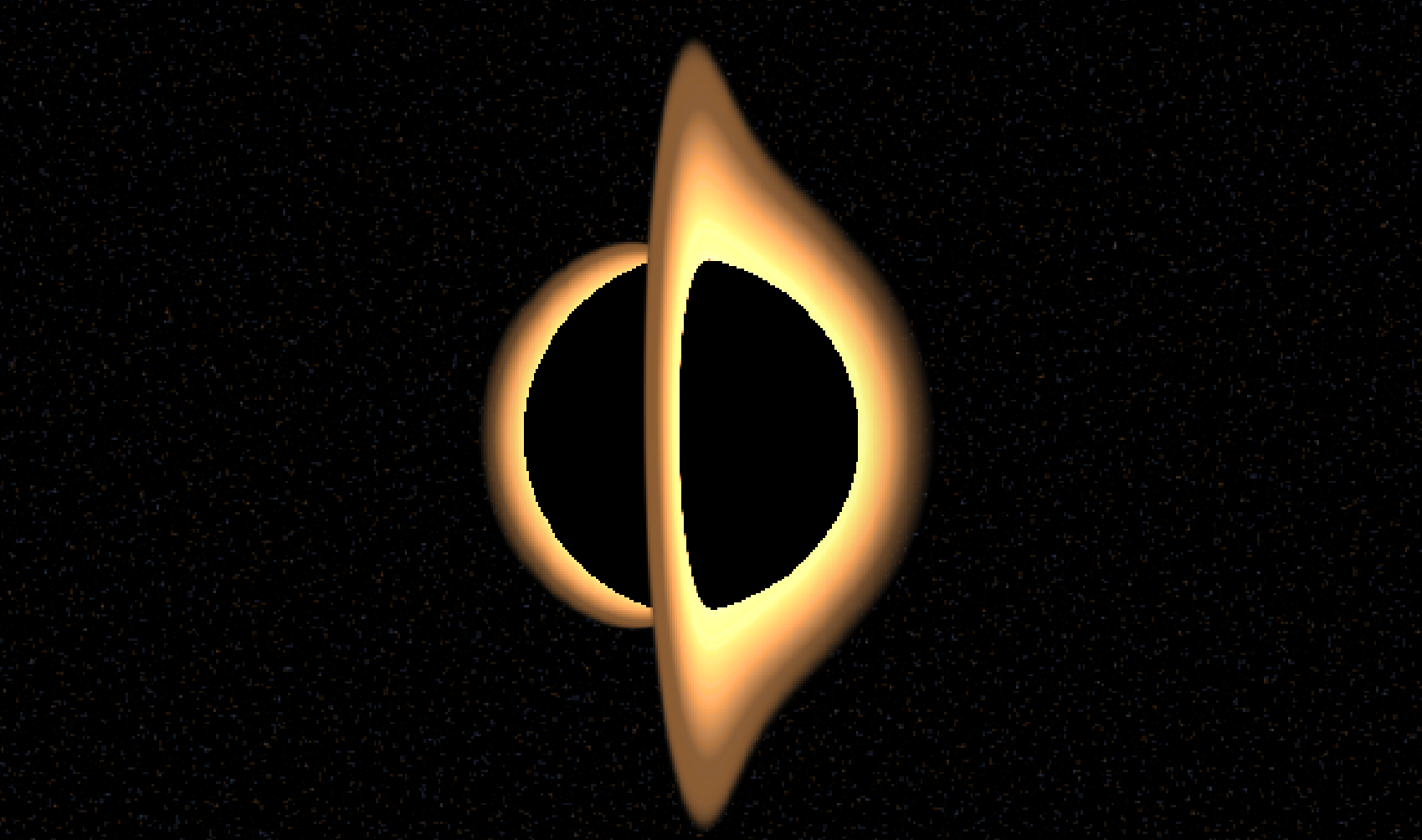

I ended up writing a ton of shaders for my other project SpaceRTS, to render stars, black holes, and galaxies. The fog of war system also uses shaders extensively.

Conclusion

There are not many libraries out there that let you write shaders in a high level language like C#, and fewer that integrate it into a full game development framework. This was a very complex project, with multiple iterations and hundreds of hours of development over the course of years. I learned a lot about CIL, decompilation, compiler architecture, and more. Worth every minute!